Anti-asexual bias

While often not as extreme as other orientations, asexual people do experience unfair hardships due to the way society is set up against their sexuality. This bias manifests itself in two interrelated ways – directly due to acephobia, and indirectly due to allonormativity.

In terms of direct bias, asexuals – just like other sexual, romantic, and gender minorities – can be victims of verbal [1a,2], physical, and sexual harassment, corrective rape and orientation-based sexual violence. Asexuals also report receiving poorer heathcare and being offered or undergoing so-called conversion therapy [1b, 1d]. In some cases asexuals may even face legal discrimination, such as in divorce or human rights laws.

On the other side, asexuals are also disadvantaged indirectly by a culture that is in some sense hostile to their existence – a phenomenon called allonormativity. Most often this manifests as erasure, which is when the existence of asexuality is ignored or outright denied.

The rest of this page goes into much more detail as to the specifics of anti-asexual bias and the evidence for its existence, as well as why talking about anit-asexual bias is important. You can read more about aphobia and how to protect asexuals in your community on Galop (an LGBT+ anti-violence charity).

Direct bias

Acephobia

Acephobia1 is a prejudicial attitude towards asexuals based on negative stereotypes, and in most cases acephobia is the source of the direct bias an asexual might experience. Examples of acephobia include [3–5] believing that asexuals:

- are less than human or against human nature,

- are deficient or broken; that it is a result of mental illness or sexual abuse,

- have just not met the "right" person,

- are confused or 'going through a phase',

- cannot experience love and have relationships,

- are just "prudes"; that asexuality is a choice rather than an orientation,

- don’t face oppression and are damaging the LGBT cause.

The following sections go into more depth for several examples of acephobia and the harmful behaviours that can result from it.

Prejudice and dehumanisation

"A strikingly strong bias against asexuals" has been documented in multiple studies [6,7]. A 2012 study published in Group Processes & Intergroup Relations [6,8] found that relative to other heterosexuals, and even relative to homosexuals and bisexuals,2 heterosexuals:

- expressed more negative attitudes toward asexuals (i.e., prejudice);

- desired less contact with asexuals; and

- were less willing to rent to or hire an asexual applicant (i.e., discrimination).

Moreover, of all the sexual minority groups studied, asexuals were the most dehumanised (that is, represented as "less human"). Asexuals were categorised not only as 'machine-like' but also 'animal-like': relatively cold and emotionless, as well as unrestrained, impulsive, and less sophisticated [6,8].

These results were later corroborated in a separate study [7], which established the Attitudes Towards Asexuals scale. This study found that negative attitudes towards asexuals were correlated with sexism, traditional gender ideologies, and conservatism. The evidence suggests that anti-asexual prejudice comes from a rigid perception of sex and gender roles, and seeing asexuals as an out-group threat (i.e. "difference as deficit") [7].

This prejudice also cannot be explained away by other factors. When other attributes of the respondents are measured studies have and that [6,7,9]

- people that were prejudiced against asexuals tended to be prejudiced against homosexuals and bisexuals (and vice versa);

- a bias against being single (which does exist [10]) does not explain the bias against asexuals;

- the bias could not be explained simply by people being unfamiliar with the term 'asexual'.

Harassment and assault

In the workplace

According to a UK Government survey [1] with over 75,000 respondents, asexuals are only slightly less likely than other sexual minorities to be a victim of harassment at work because of their orientation [1a]. The survey asked "In the past 12 months, did you experience any of the following in your workplace because you are LGBT or others thought you were LGBT?"3 The table below shows the rates across all orientations [1a].

![Response rates from the National LGBT Survey [1a] for gay / lesbian people, bisexuals, pansexuals and asexuals.](images/workplace_harassment.png)

In universities

A 2015 study commissioned by the American Association of Universities [18] found that (in a university setting) asexuals were more likely than homosexuals or heterosexuals (though less likely than bisexuals) to experience

- non-consensual sexual contact involving physical force or incapacitation [18, p.102];

- non-consensual sexual contact involving absence of affirmative consent [18, p.103];

- harassment [18, p.104]

- intimate partner violence [18, p.105];

- stalking [18, p.106].

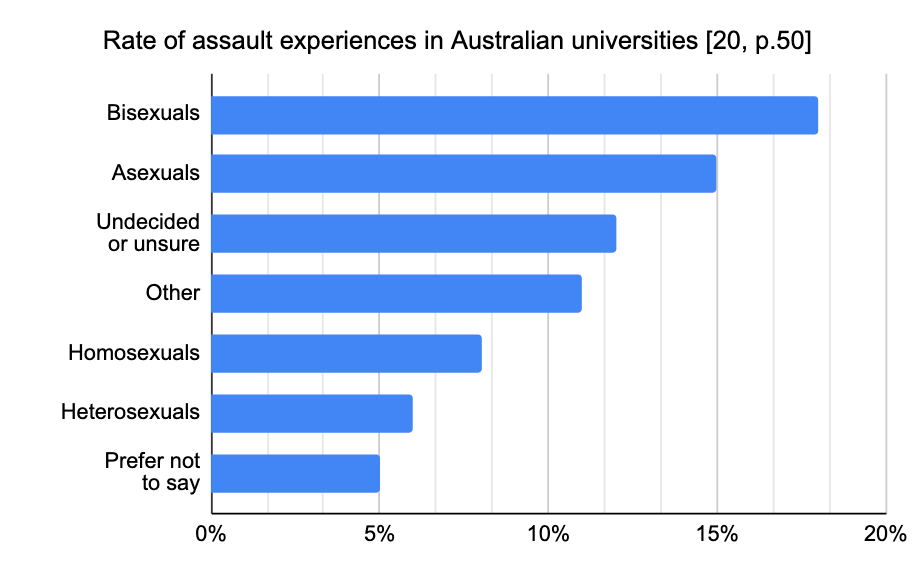

A similar study looking at 30,000 students in Australian universities [20] found that bisexual and asexual students were substantially more likely to be victims of sexual assault than homosexual ones (who were also more likely to experience assault than heterosexuals). The rates by orientation are shown in chart below [20, p.50]. The same study found that asexuals (along with other sexual minorities) were more likely than heterosexuals to experience sexual harassment at university [20, p.40].

Healthcare

There is evidence of systematic issues with the way that healthcare systems interact with asexuals, and in particular those that are open about their sexuality. A UK Government survey [1] found that asexuals reported (as a result of their orientation)

- avoiding treatment or accessing services due to fear or discrimination or intolerant reactions;

- specific needs being ignored or not taken into account;

- inappropriately being referred to specialist services;

- discrimination or intolerant reactions from staff;

- unwanted pressure or being forced to undergo a medical or psychological test;

- inappropriate questions or curiosity;

all at higher rates than any other sexual orientation (with the notable exception of "Queer") [1b]. The pressure to undergo unwanted medical treatment is where this difference is the most severe, where in some cases asexuals report this happening at approximately 5 times the rate of other sexual minorities.

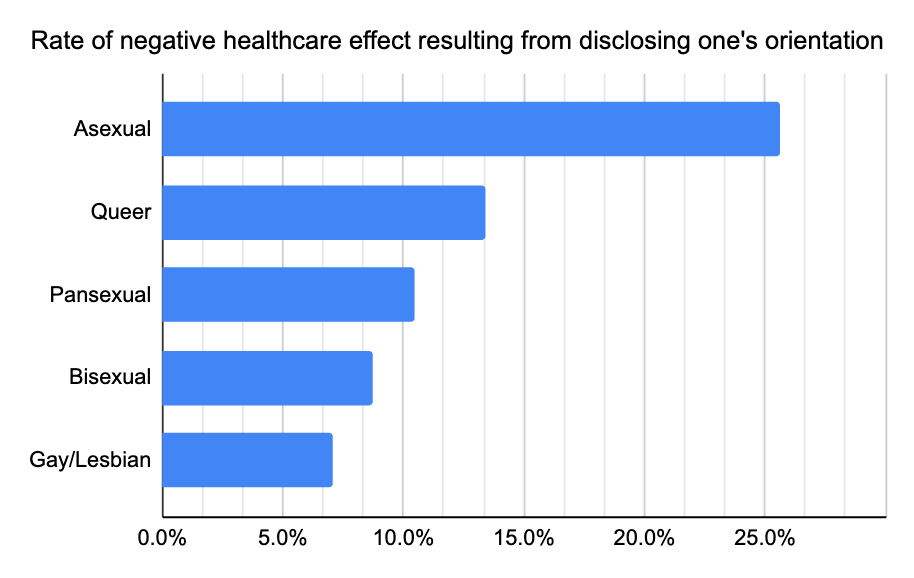

Effect of disclosure on care

The same survey [1] asked "In the past 12 months, did being open about your sexual orientation with healthcare staff have an effect on your care?" The percentage of respondents that answered "Yes, negative effect" across all sexual orientations is shown in figure 3 [1c].

The figures show that asexuals are significantly more likely to have their care negatively impacted than any other sexual orientation. At the same time, asexuals had the lowest rate of reporting there being a positive effect from disclosing their orientation. In fact, asexuals were the only sexuality demographic to report a negative effect at a higher rate than a positive effect.

Conversion therapy

Asexuals are also the most likely to have been offered or undergone so-called conversion therapy. The rates across different sexual orientations is shown below [1d].6

- Asexuals: 10.2%

- Gay/Lesbian: 7.6%

- Queer: 7.4%

- Pansexual: 6.6%

- Bisexual: 5.2%

- Other: 7.6%

Of course, these figures should not be taken to imply that conversion therapy is any more or less damaging to any given asexual compared with other orientations.

Allonormativity

'Allonormativity' is a term used in the a-spectrum community to refer to the fact that allosexuality8,9 is implicitly considered normative by society – that is, allosexuality is prescriptively defined as good or desirable. At a broader level, allonormativity puts a label to the cluster of cultural beliefs that are harmful towards asexuals. Allonormativity forms an invisible culturally dominant ideology which is both unquestioned and reinforced by cultural attitudes and media. 'Amatonormativity' similarly refers to society's normative prescriptions about romantic ideals, which affect aromantics in addition to bi/pan/poly-romantics.

The false beliefs of this ideology are precisely the assumptions that asexuality as a social movement aims to refute, many of which are listed explicitly in What is asexuality?. In broad stokes, these assumptions assert that

- everyone experiences sexual attraction,

- everyone wants or likes sex,

- romance and sex cannot be separated, and

- sexual and romantic relationships deserve more celebration and recognition than platonic ones.

It might seen strange to label cultural anti-asexuality beliefs in this way, and in particular to call them an ideology – after all, it's not as if these beliefs pick out asexuals as the target of violence and oppression. However, this way of thinking underestimates the degree to which we do live in a world that promotes or at least tacitly endorses explicitly anti-asexual messages on a regular basis. For example, it's entirely normal for someone to say "sex is what makes us human", genuinely mean it, and not be challenged in any way – even if they do so on TV or in print.

Remaining unnamed is one of the primary ways in which this ideology perpetuates itself, so by calling attention to allonormativity the term can be a vector for change that benefits everyone, asexual or otherwise. Erasure

One of the most common ways that allonormativity manifests itself is through asexual erasure, which is when the existence is ignored or otherwise denied.10 In its simplest form, asexual erasure exists in statements like "I support you whether you're attracted to men, women, or both" or "Is he gay, or straight?"11; or when surveys do not include an option for asexual.12 It's common for textbooks and courses on human sexuality to entirely fail to mention asexuality, and the medical and psychotherapy profession also been slow to make any accommodation for its existence. More generally, people may also ignore or disbelieve evidence of a person being asexual, the existence of the struggles or unique experience of being asexual, and the presence of asexuality in history.

Media is a common source of asexual erasure. TV in particular, by it's long-running nature, has a tendency to eventually make characters allosexual in an attempt to retain interest. This of course implies that asexuality, or a lack of interest in romance, is boring, as well as that asexuality is simply a phase. For a concrete example of this, one can consider the character of Jughead from Archie comics. In several iterations of the comics Jughead has been clearly coded as aromantic asexual, and was confirmed to be asexual explicitly in the 2015 reboot [21]. When the comic was adapted to TV the producers decided to make Jughead allosexual, because they must not that thought Judhead's orientation was an important character trait.

The problem of asexual erasure exists even in the LGBT+ community to an extent. For example, use of the "LGBT" acronym itself erases asexuality because it neither falls under lesbian, gay, bisexual, or trans. Even extended acronyms like LGBTQIA can cause erasure over the contention that the "A" does not stand for asexual and aromantic, but rather "ally". (This is why the more inclusive GSRM – Gender Sexual and Romantic Minorities – is sometimes preferred.) But the problem also goes deeper. While it's understandable that more focus is given to other parts of the LGBT+ community due to them often experiencing more minority stress, asexuality is all-too-often dropped altogether from educational material and more broadly the entire conversation surrounding prejudice against sexual minorities.

The harm caused by allonormativity

Allonormativity is the root cause of many of the most painful and confusing aspects of being asexual.

Most directly, it places asexuals on the outside of society, by implicitly saying that their experience doesn't matter and isn't worth talking about. What's insidious about this is the feeling of isolation it can create – if no one ever talks about it, it's common for asexuals to feel alone, as if they are the only person that feels the way they do. This social isolation leaves them vulnerable to internalising harmful messages about themselves, like that they are broken, incomplete, infantile, or less capable and deserving of love (romantic or otherwise).

One of the most common experiences among asexuals can be summed up as "I didn't know it was an option". Compared to other orientations, many asexuals do not discover what their orientation is until much later in life – it's not uncommon for asexuals to go decades of their adult life thinking they are straight, gay, or bisexual. Plenty of asexuals even have long-term sexual relationships without knowing what their orientation is. To a large extent, this gap is only possible because erasure exists. People who are questioning their orientation typically try to decide between these more well-known sexualities simply because they haven't heard of the concept of asexuality before. For such people, years or even decades of confusion and pain could have been saved if asexuality were talked about even very occasionally in popular culture.

It is no surprise that many asexuals feel the need to become someone they're not in order to fit in – or even to agree to sex they don't want because they don't even realise they don't want it, or that they are allowed not to want it.

The impact of bias

Individuals from oppressed social groups, such as sexual and gender minority people, experience excess stress because of their minority status (or statuses), which can lead to, exacerbate, and maintain mental and physical health problems. Studies show that asexuals are affected in this way to the same – or even a greater – degree than other minority sexual orientations [11]. Asexuals have also been found to have the lowest life-satisfaction of any sexual orientation (tying with pansexuals) [1].

Anxiety

A study measured the average Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) score across different orientations, with the results below [11].7

- Demisexual: 11.56

- Pansexual: 10.13

- Bisexual: 9.92

- Asexual-spectrum: 9.57 (aggregate of demi- and a-sexuals)

- Queer: 9.56

- Asexual: 9.24

- Gay/Lesbian: 7.50

- Heterosexual: 6.16

GAD-7 scores range from 0–21, with 5, 10, and 15 representing mild, moderate, and severe anxiety symptoms respectively. GAD-7 scores have robust psychometric properties and have been validated in the general population [12,10].

Not only do asexuals have a higher rate of anxiety than heterosexuals, "the available evidence seems to suggest that those feelings are a result of prejudice and discrimination against asexuals" [14]. In fact, the higher rate of anxiety was documented only in the subset of asexuals that have had phobic experiences [15]. There is no known link between asexuality and trauma, and no correlation between asexuality and psychopathology, which suggests that asexuality in-and-of-itself is not a mental disorder, the underlying cause of the anxiety, or a result of the anxiety [14,15].

Suicidality

The rate of suicidality among asexuals is particularly alarming. One study [19, p.142] found that 26% of asexual individuals had some suicidal feelings in the past two weeks, which was slightly higher than other minority orientations (24%) and significantly higher than heterosexuals (12%). The researchers noted that the increased suicide risk seems to be in response to negotiating sexual identity within the larger social picture, and may be associated with risk factors including substance abuse, family dysfunction, interpersonal conflict surrounding sexual orientation and non-disclosure of sexual orientation [19, p.147]. The same study also found that asexuals were the more likely than heterosexuals to report symptoms of mood or anxiety disorders [19, p.141].

The figures are especially striking when considering the presence of suicidal thoughts across the entire lifespan. According to the 2016 Asexual Community Survey4 [16]:

- 50% of asexuals have "seriously considered suicide";

- 40% of cis asexuals have "seriously considered suicide";

- 14% of asexuals have attempted suicide;

- 10% of cis asexuals have attempted suicide.

For comparison, the rate of attempted suicide among LGBT youth is 10% [17].

A call to action

The factors discussed above show that asexuals are disadvantaged in many areas of life. The evidence suggests that this personal and cultural hostility can negatively impact asexuals' self-esteem, social mobility, community acceptance and even their health and safety – with rates of anxiety and suicidality being either comparable to or even more severe than other sexual, romantic, and gender minorities. At the same time, anti-asexual prejudice also correlates with homophobia and transphobia, and is caused by the same underlying beliefs.

There are therefore two distinct calls to action against anti-asexual bias, mirroring the two ways – direct and indirect – that the bias manifests in the first place.

First, while understanding that the experience of asexuals is necessarily different than that of other sexual, romantic, and gender minorities, we should be empathetic towards the issues that asexuals deal with, and not seek to minimise their importance in comparison to the issues facing others. We should not be asking whether asexuals suffer the most, or in the right way, for that suffering to matter – whether you want to call these things oppression, or discrimination, or neither, they are real, and the consequences can literally be the difference between life and death.

And second, anti-asexual bias emerges from the same cultural place as – and is in some sense inseparable from – the well-documented bias against other sexual, romantic, and gender minorities. To be against homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia is therefore also to be against aphobia; and to fight aphobia is to fight the underlying cultural attitudes that impact all sexual, romantic, and gender minorities.

Footnotes

- There is an analogous term, arophobia which refers to prejudice against aromantics. Aphobia is a boarder term that refers to prejudice against people on any of the a-spectra.

- The sample group in the study was university / college students, which likely explains what seems to be overall more positive attitudes towards homosexuals and bisexuals than might be expected.

- Note that in the survey, "LGBT" was defined as an "umbrella term to describe people who self-identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or as having any other minority sexual orientation or gender identity, or as intersex".

- It should be noted that this survey was done online and may be subject to sample bias. However, given the lack of research in the area, it is currently the largest survey into this question and represents our current best knowledge on the matter.

- A significant proportion of asexuals are also trans (approximately 30% [16]). Because this could confound the effect of being asexual in-and-of-itself, we have used data for cis-only people where possible. Otherwise, it would be reasonable to ask if any given effect can be attributed solely to the presence of trans people in the sample.

- The figures quoted here are the sum of those that report being offered conversion therapy and those that report undergoing it. The percentage of people that undergo conversion therapy is necessarily lower – in the case of asexuality, 2.3%, which is the highest among any orientation (tying with gay/lesbian) [1d].

- These figures by orientation are only available with cis and trans respondents aggregated together. However, trans respondents had an average score of 10.29 (in aggregate) or 7.57 (for non-cis heterosexuals). Neither figure can be used to explain the average score among the asexual-spectrum of 9.57 (using that approximately 30% of asexuals report being trans [16]).

- The term 'allonormativity' can be ambiguous, since it covers all of the a-spectra – that is, it can mean allosexual-normativity, alloromantic-normativity, allosensual-normativity, and so on. However, in most cases 'allonormativity' is used to refer to allosexual-normativity, since 'amatonormativity' can be used in the romantic case.

- For definition of 'allosexuality' and further discussion about this term see The term 'allosexual'.

- This idea is analogous to the perhaps more familiar bisexual erasure. The fact that bisexual erasure is significantly more well-known and discussed than asexual erasure (even having its own Wikipedia page) itself speaks to the fact that asexuals and the issues they face are rarely talked about.

- Of course, these particular statements also engage in the erasure of gender identities and bisexuality respectively.

- For a mainstream example of this, the 2019 EU LGBTI survey (at the time the largest survey of LGBTI people ever conducted) did not include an option of asexual, and in fact did not even record the response of anyone who didn't identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, or intersex.

See also

Are asexual people LGBT? Are asexual people straight?References

- [1]: Government Equalities Office (2017). National LGBT Survey.

- [1a]: Data viewer: Experiences in the workplace / Incidents, by Cisgender / Sexual orientation.5 There were approximately 75,000 respondents.

- [1b]: Data viewer: Healthcare / Public healthcare / Incidents due to sexual orientation, by Cisgender / Sexual orientation.5

- [1c]: Government Equalities Office (July 2018). National LGBT Survey: Research Report, p.176. ISBN 978-1-78655-671-4. Figures are of cis-gendered respondents only.6 There were approximately 34,000 respondents.

- [1d]: Government Equalities Office (July 2018). National LGBT Survey: Research Report, p.85. ISBN 978-1-78655-671-4. Figures are of cis-gendered respondents6 who reported either having or being offered conversion therapy. There were approximately 91,000 respondents.

- [2]: Stephanie B., Gazzola & Morrison, Melanie (2012). Asexuality: An emergent sexual orientation. ResearchGate.

- [3]: Acephobia & Anti-asexual hate crime (2019). Galop.

- [4]: Carrigan, Mark (15 August 2011). There's more to life than sex? Difference and commonality within the asexual community. Sexualities. 14 (4): 462–478. doi:10.1177/1363460711406462.

- [5]: Van Houdenhove, Ellen; Gijs, Luk; T’Sjoen, Guy; Enzlin, Paul (17 April 2014). Stories About Asexuality: A Qualitative Study on Asexual Women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 41 (3): 262–281. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2014.889053.

- [6]: MacInnis, Cara C.; Hodson, Gordon (2012). Intergroup bias toward "Group X": Evidence of prejudice, dehumanization, avoidance, and discrimination against asexuals. Group Processes Intergroup Relations. 15 (6): 725–743. doi:10.1177/1368430212442419.

- [7] Hoffarth, Mark R.; Drolet, Caroline E.; Hodson, Gordon; Hafer, Carolyn L. (26 May 2015). Development and validation of the Attitudes Towards Asexuals (ATA) scale. Psychology & Sexuality. 7 (2): 88–100. doi:10.1080/19419899.2015.1050446.

- [8]: Gordon Hodson (2012). Prejudice Against “Group X” (Asexuals). (Discussion of citation [3] by one of the authors intended for a more general audience). Psychology Today.

- [9]: Bella DePaulo (2020). Biased Against Asexuals? Let Me Count the Ways. Psychology Today.

- [10]: Pignotti, Monica; Abell, Neil (6 March 2009). The Negative Stereotyping of Single Persons Scale. Research on Social Work Practice. 19 (5): 639–652. doi:10.1177/1049731508329402. ISSN 1049-7315.

- [11]: Borgogna, Nicholas C.; McDermott, Ryon C.; Aita, Stephen L.; Kridel, Matthew M. (March 2019). ,i>Anxiety and depression across gender and sexual minorities: Implications for transgender, gender nonconforming, pansexual, demisexual, asexual, queer, and questioning individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 6 (1): 54–63. doi:10.1037/sgd0000306.

- [12]: Löwe, Bernd; Decker, Oliver; Müller, Stefanie; Brähler, Elmar; Schellberg, Dieter; Herzog, Wolfgang; Herzberg, Philipp Yorck (March 2008). Validation and Standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the General Population. Medical Care. 46 (3): 266–274. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093.

- [13]: Plummer, Faye; Manea, Laura; Trepel, Dominic; McMillan, Dean (March 2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry. 39: 24–31. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005.

- [14]: Bella DePaulo (2016). Asexuality Is a Sexual Orientation, Not a Sexual Dysfunction. Psychology Today.

- [15]: Brotto, Lori A.; Knudson, Gail; Inskip, Jess; Rhodes, Katherine; Erskine, Yvonne (11 December 2008). Asexuality: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 39 (3): 599–618. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9434-x.

- [16]: Caroline Bauer et al (2018). 2016 Asexual Community Survey Summary Report, p. 36. Asexual Community Survey Team.

- [17]: Suicide Prevention Resource Center (2008). Suicide risk and prevention for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Newton, MA: Education Development Center, Inc.

- [18]: Cantor, David et al (2015). Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct. Westat.

- [19]: Yule, Morag A.; Brotto, Lori A.; Gorzalka, Boris B. (7 March 2013). Mental health and interpersonal functioning in self-identified asexual men and women. Psychology and Sexuality. 4 (2): 136–151. doi:10.1080/19419899.2013.774162.

- [20]: (2017). Change the course : national report on sexual assault and sexual harassment at Australian universities. Australian Human Rights Commission. ISBN 978-1-921449-86-4.

- [21]: Abraham Riesman (2016). Archie Comic Reveals Jughead Is Asexual. Vulture, Vox Media.